10th Annual Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage Celebrates an Oft-Hidden Park History

Published in two installments in The Mammoth Times on August 25, 2022 and September 1, 2022

Highway 120, or the Tioga Road, shapes many human lives today as it connects the Eastern Sierra to Yosemite National Park, a point of passage that provides economic livelihood to many of the small tourist towns in the region we call home. But the history of this road itself also points to another human story tied to the land — in 1882, this road was constructed by a group of workers predominantly Chinese. Around 250 Chinese and 90 Caucasian workers, as well as 100 Chinese blasters, completed this 56-mile road in 130 days.

This story is just one small piece of the rich and complex history of Chinese immigrants in the Yosemite area. What can tracing this story help us learn about the place? For one thing, stories like this are not relegated to the past, they make an impact on the modern day, too. At the end of this past July, park rangers, members of historical societies, educators, activists, and others gathered in Lee Vining, Tuolumne Meadows, and Yosemite Valley for the 10th annual Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage, an event founded in 2013 to honor and uplift Chinese-American history in the Yosemite area. Through the lens of history and preserving stories from the past, organizers and attendees described the modern-day power of the continuation of this pilgrimage, as a means of building and maintaining community, of sharing stories and the education they bring with them, of energizing and fueling movements for racial justice, and more.

The pilgrimage makes up one facet of broader efforts to document Chinese history, and other histories that have historically been relegated to the margins, in Yosemite. And this theme is not unique only to the park itself — across the Eastern Sierra, human histories are inscribed in this landscape that so many treasure. Efforts to better represent those stories and weave them into the love for the natural world that fuels so much of this region’s economy and identity are becoming larger parts of these places today.

As one such effort itself, the Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage is put together by the Park Service, the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC), the National Parks Conservation Association, and other Chinese historical societies from across California. The pilgrimage is six days long, and consists of ranger-led walks around the park, interpretive education about Chinese history in key sites, a potluck, and a 3-day backpacking trip to summit Sing Peak, among other activities.

“A lot of people come here because the National Parks are incredibly beautiful, there’s something special about this landscape, protecting wildlife and important species and ecosystems,” said Yenyen Chan, a Yosemite National Park Interpretive Ranger who has extensively researched and documented Chinese history in Yosemite and helped found and organize the pilgrimage. “But our mission is dual. It’s also protecting the cultural history and cultural resources… From our National Parks, we actually learn a lot about our country’s history, and have this opportunity to really shed some light on the stories that might not have gotten told.”

Jack Shu, a retired California state park superintendent and ranger who also founded the event and continues to help organize it, spoke on the impact that telling the story of Chinese immigrants in Yosemite “better, and more times” can have. “I think now, the story that… Chinese Americans, Asian Americans, and many other people, have been involved with the building of Yosemite for a long time, that is going to be a notion that is going to start sticking more — that it took more than John Muir,” he said.

Tracing Chinese History in the Yosemite Area – compiled based on a number of public sources written by Chan

Chinese immigrants first began to arrive in large numbers in California around 1848, when gold was first discovered in the foothills. Shortly after in 1850, the Foreign Miners Tax, which placed a tax of $20 per month on all miners from outside the United States, was passed, and even after being fought against and eventually repealed, later tax laws still took target specifically at Chinese and Mexican miners. State taxes thus led to a shift in labor patterns; Chinese Americans began to look for other types of work.

Some of these new types of work included the labor that Yosemite National Park was looking for at that moment in time, cooks and other people to staff hotels in the park, and people to construct the roads and other infrastructure it was beginning to develop. And so today, much of the credit for the park’s development and success is held by the labor of Chinese immigrants, whose work was essential, creative, and powerful, but oftentimes hidden.

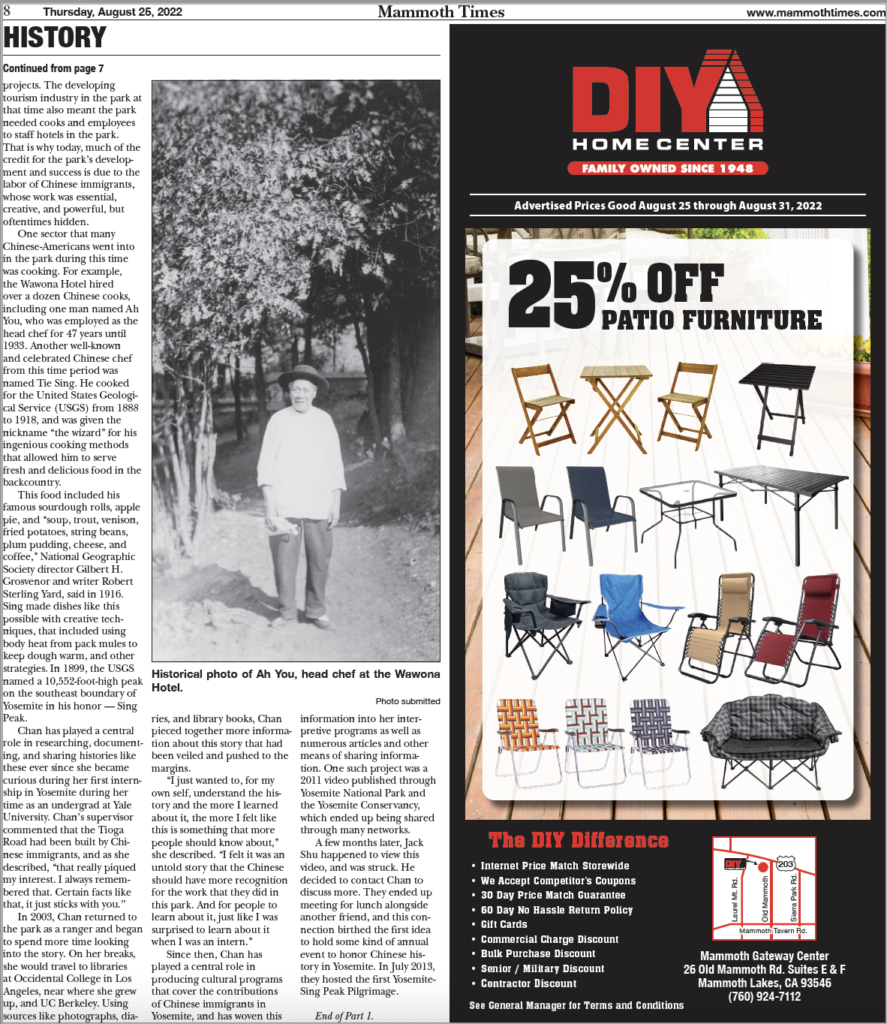

One sector that many Chinese-Americans went into in the park during this time was cooking. For example, the Wawona Hotel hired over a dozen Chinese cooks, including one man named Ah You, who was employed as the head chef for 47 years until 1933. Another well known and celebrated Chinese chef from this time period was named Tie Sing. he cooked for the United States Geological Service (USGS) from 1888 to 1918, and was given the nickname “the wizard” for his ingenious cooking methods that allowed him to serve fresh and delicious food in the backcountry.

This food included his famous sourdough rolls, apple pie, and “soup, trout, venison, fried potatoes, string beans, plum pudding, cheese, and coffee,” as National Geographic Society director Gilbert H. Grosvenor and writer Robert Sterling Yard, described in 1916. Sing made dishes like this possible with his creative techniques like using body heat from pack mules to keep dough warm, and other strategies. In 1899, the USGS named a 10,552 foot peak on the southeast boundary of Yosemite in his honor — Sing Peak, which the latter part of the pilgrimage centers around.

As mentioned in the introduction to the article, Chinese immigrants also played a critical role in the construction of two main Yosemite roads, the Wawona Road and the Tioga Road.

Chan has played a central role in researching, documenting, and sharing histories like these ever since she became curious during her first internship in Yosemite during her time as an undergrad at Yale University. Chan’s supervisor commented that the Tioga Road had been built by Chinese immigrants, and as she described, “that really piqued my interest. I always remembered that. Certain facts like that, it just sticks with you.” In 2003, Chan returned to the park as a ranger and began to spend more time looking into the story. On her breaks, she would travel to libraries at Occidental College in Los Angeles, near where she grew up, and UC Berkeley. Using sources like photographs, diaries, and library books, Chan pieced together more information about this story that had been veiled and pushed to the margins.

“I just wanted to, for my own self, understand the history and the more I learned about it, the more I felt like this is something that more people should know about,” she described. “I felt it was an untold story that the Chinese should have more recognition for the work that they did in this park. And for people to learn about it, just like I was surprised to learn about it when I was an intern.”

Since then, Chan has played a central role in producing cultural programs that cover the contributions of Chinese immigrants in Yosemite, and has woven this information into her interpretive programs as well as numerous articles and other means of sharing information. One such project was a 2011 video published through Yosemite National Park and the Yosemite Conservancy, which ended up being shared through many networks.

A few months later, Jack Shu happened to view this video, and was struck. He decided to contact Chan to discuss more. They ended up meeting for lunch alongside another friend, and this connection birthed the first idea to hold some kind of annual event to honor Chinese history in Yosemite. In July 2013, they hosted the first Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage.

While the event has changed some in content and duration over the years, its core idea has remained the same, and it has brought in a combination of returning participants and new ones everyone. This year, according to Shu, the group was about one third first-timers, and two thirds participants who were returning again.

The 2022 Pilgrimage

The 2022 event consisted of history talks and star walks with rangers, a hike around May Lake and other interpretive activities in Yosemite. On the evening of July 30th, participants gathered in the Lee Vining community center for presentations and a potluck.

There, illustrator Rich Lo spoke about his artwork for the children’s book “Mountain Chef” and his journey as a Chinese American artist. Chef David Soohoo then presented with a historical talk and a demonstration of Cantonese cuisine cooking. His presentation wove together information about the modern day, such as the negative impact of Covid-19 and race-based hate on Chinese restaurants in California, as well as historical aspects, such as the fact that one newspaper archive from Sacramento can show us how a Chinese New Year banquet was held there in 1882, and what kinds of food were served. Popular dishes in that location during that time included some locally-sourced ingredients, like water snails from the Stockton and Tracy rivers.

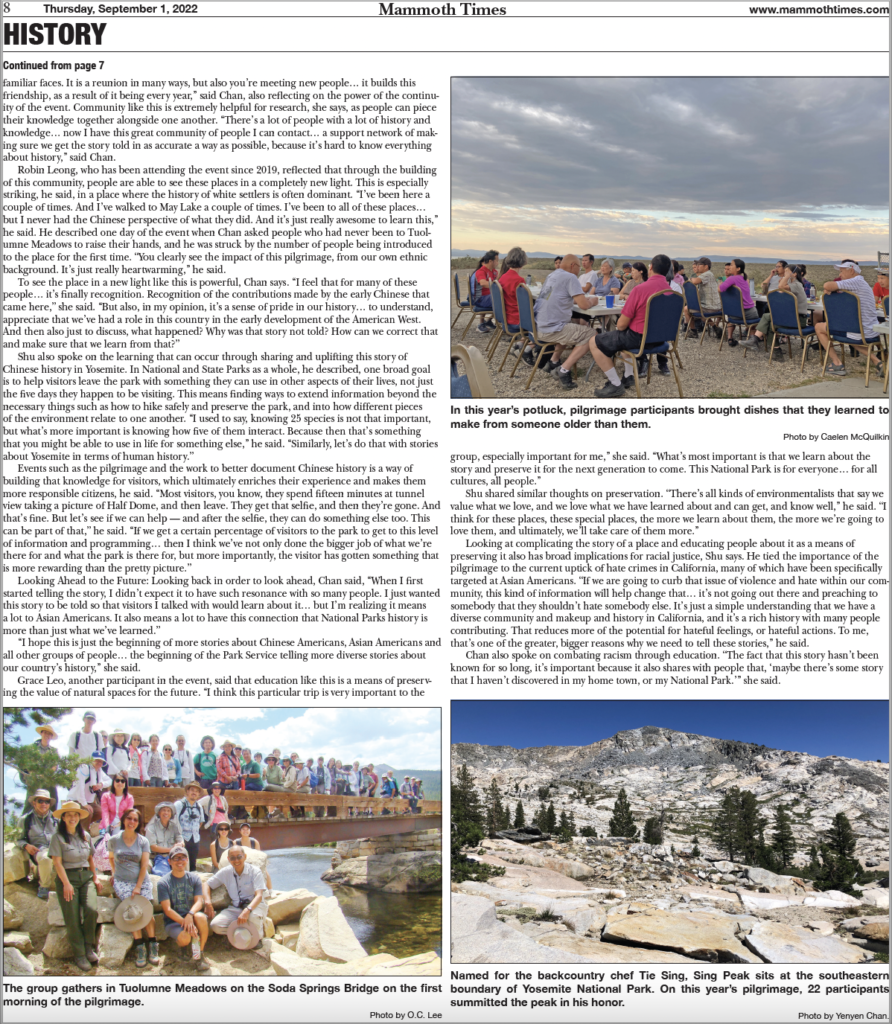

In a utilization of the Lee Vining community center whose wide variety of uses points to the diversity and complexity of communities in this area, the group then held a potluck where people brought dishes with the theme “something I learned to cook from someone older than me.” The tables were filled with delicious food, and handouts with the recipe for Gam Saan Jook, or unhulled long grain rice congee, a popular dish among Chinese workers with higher health benefits.

On the final day of the pilgrimage before the backpacking trip to Sing Peak, the group walked around Yosemite Valley and Wawona with Chan, visiting sites such as the “Chinese Quarters” which are on the south side of Yosemite Valley, to the east of where Sentinel Bridge is located today, and visit to Yosemite’s Chinese Laundry Exhibit in Wawona. At each of the sites, Chan handed around copies of the historical documents linked to those places, such as copies of the preserved notes and receipts from Chinese employees working at the Sentinel Hotel and other hotels in the area.

In all the group activities like this, a sense of community felt clear, with people chiming in with information like “my dad collected those same jars,” or asking another attendee about using their artwork to support a local campaign.

After this last day in the valley, those who would join the backpacking trip to Sing Peak gathered to begin. This year, 22 people attempted Sing Peak and 22 summited, said Shu. The trip “provided that kind of challenge for those who wanted to commemorate the contributions of Chinese Americans, and specifically Tie Sing,” he said. “We commemorate and honor Tie Sing, and… it has this personal reward of making it up Sing Peak.”

A Lasting Impact

On the last day of the pilgrimage before the start of the Sing Peak backpacking trip, attendees gathered in a closing circle to share what they had learned in the event and what it meant to them. The thoughts shared in this circle encompass much of what the event organizers explain the event represents. Attendees spoke on their gratitude for being able to learn through people’s different perspectives, all of which are shaped by family history, on their gratefulness for their ancestors’ contributions and what it means to confront the fact that credit was never given for them, on the way that history is something we are still writing and discovering, an ongoing process. One attendee reflected on the way that they had come to learn about Yosemite as a place of power, a place in which walking and learning can help one imagine what reclaiming their history could look like. Other reflections covered the importance of storytelling and how the pilgrimage can live on through good storytelling, and the importance of the fact that the event is fun, a time for building and finding friendships and connections. Yet others reflected on the courage and resilience that their ancestors who came here first must have carried with them, and how those sentiments still live on.

Shu described that many of these lessons are made possible by the fact that the event occurs annually. “That’s what I think an annual event does, it prompts us to keep going and [prompts] more interest, and for people to start paying attention to it,” he said. “Why do we have birthday parties every year? We celebrate your birthday every year, same day. Or any other kind of event that is annual — we do it and we make it a point.”

“I look forward to seeing familiar faces. It is a reunion in many ways, but also you’re meeting new people… it builds this friendship, as a result of it being every year,” said Chan, also reflecting on the power of the continuity of the event. Community like this is extremely helpful for research, she says, as people can piece their knowledge together alongside one another. “There’s a lot of people with a lot of history and knowledge… now I have this great community of people I can contact… a support network of making sure we get the story told in as accurate a way as possible, because it’s hard to know everything about history,” said Chan.

Robin Leong, who has been attending the event since 2019, reflected that through the building of this community, people are able to see these places in a completely new light. This is especially striking, he said, in a place where the history of white settlers is often dominant. “I’ve been here a couple of times. And I’ve walked to May Lake a couple of times. I’ve been to all of these places… but I never had the Chinese perspective of what they did. And it’s just really awesome to learn this,” he said. He described one day of the event when Chan asked people who had never been to Tuolumne Meadows to raise their hands, and he was struck by the number of people being introduced to the place for the first time. “You clearly see the impact of this pilgrimage, from our own ethnic background. It’s just really heartwarming,” he said.

To see the place in a new light like this is powerful, Chan says. “I feel that for many of these people… it’s finally recognition. Recognition of the contributions made by the early Chinese that came here,” she said. “But also, in my opinion, it’s a sense of pride in our history… to understand, appreciate that we’ve had a role in this country in the early development of the American West. And then also just to discuss, what happened? Why was that story not told? How can we correct that and make sure that we learn from that?”

Shu also spoke on the learning that can occur through sharing and uplifting this story of Chinese history in Yosemite. In National and State Parks as a whole, he described, one broad goal is to help visitors leave the park with something they can use in other aspects of their lives, not just the five days they happen to be visiting. This means finding ways to extend information beyond the necessary things such as how to hike safely and preserve the park, and into how different pieces of the environment relate to one another. “I used to say, knowing 25 species is not that important, but what’s more important is knowing how five of them interact. Because then that’s something that you might be able to use in life for something else,” he said. “Similarly, let’s do that with stories about Yosemite in terms of human history.”

Events such as the pilgrimage and the work to better document Chinese history is a way of building that knowledge for visitors, which ultimately enriches their experience and makes them more responsible citizens, he said. “Most visitors, you know, they spend fifteen minutes at tunnel view taking a picture of Half Dome, and then leave. They get that selfie, and then they’re gone. And that’s fine. But let’s see if we can help — and after the selfie, they can do something else too. This can be part of that,” he said. “If we get a certain percentage of visitors to the park to get to this level of information and programming… then I think we’ve not only done the bigger job of what we’re there for and what the park is there for, but more importantly, the visitor has gotten something that is more rewarding than the pretty picture.”

Looking Ahead to the Future

Looking back in order to look ahead, Chan said, “When I first started telling the story, I didn’t expect it to have such resonance with so many people. I just wanted this story to be told so that visitors I talked with would learn about it… but I’m realizing it means a lot to Asian Americans. It also means a lot to have this connection that National Parks history is more than just what we’ve learned.”

“I hope this is just the beginning of more stories about Chinese Americans, Asian Americans and all other groups of people… the beginning of the Park Service telling more diverse stories about our country’s history,” she said.

Grace Leo, another participant in the event, said that education like this is a means of preserving the value of natural spaces for the future. “I think this particular trip is very important to the group, especially important for me,” she said. “What’s most important is that we learn about the story and preserve it for the next generation to come. This National Park is for everyone… for all cultures, all people.”

Shu shared similar thoughts on preservation. “There’s all kinds of environmentalists that say we value what we love, and we love what we have learned about and can get, and know well,” he said. “I think for these places, these special places, the more we learn about them, the more we’re going to love them, and ultimately, we’ll take care of them more.”

Looking at complicating the story of a place and educating people about it as a means of preserving it also has broad implications for racial justice, Shu says. He tied the importance of the pilgrimage to the current uptick of hate crimes in California, many of which have been specifically targeted at Asian Americans. “If we are going to curb that issue of violence and hate within our community, this kind of information will help change that… it’s not going out there and preaching to somebody that they shouldn’t hate somebody else. It’s just a simple understanding that we have a diverse community and makeup and history in California, and it’s a rich history with many people contributing. That reduces more of the potential for hateful feelings, or hateful actions. To me, that’s one of the greater, bigger reasons why we need to tell these stories,” he said.

Chan also spoke on combating racism through education. “The fact that this story hasn’t been known for so long, it’s important because it also shares with people that, ‘maybe there’s some story that I haven’t discovered in my home town, or my National Park.’” she said.