Published in The Amherst Student on March 29, 2023

“Auxiliary Services has worked through the night to clear the campus walkways and roads.” When students open their inboxes during the winter, we’re often greeted by this phrase — a snowstorm hits, and we await the announcement about whether campus is clear enough to continue operations as normal.

The process that makes this possible takes place behind the scenes for students but occupies center stage for others in the college community. To learn more about it, The Student spoke with staff who work on snow removal at the college.

These staff work within the custodial and grounds departments, which together oversee snow removal. According to Supervisor of Landscape and Grounds Kenneth Lauzier and Custodial Supervisor Liz Pereira, the custodial department is responsible for clearing snow on walkways, staircases, and entrances to the dorms they clean and maintain, as well as the general surroundings of those buildings. Meanwhile, the grounds department oversees roads, parking lots, driveways, sidewalks, and “floating staircases,” or staircases that are not immediately attached to buildings.

Staff working in snow removal said that the preparation and work necessary to clear snow depends on the timing and severity of the storm, but consistently requires different types of labor. Essential staff on hourly wages also spoke on the labor that snow removal adds to their schedules and what this means for how they see their pay. And more broadly, staff shared stories about how snow removal work has shaped their understandings of the Amherst campus.

Before the Storm

According to Lauzier, the process of preparing for a snow storm typically begins about a week before it is predicted to hit. He described “constantly toggling back and forth every five minutes between every possible weather app” as soon as snow appears on the radar. No matter how large the snow storm is, custodial and grounds will anticipate some work to clear it. But to get more clarity on how much snow is expected, the college receives special briefings from the National Weather Service that include confidence ratings in their predictions for the storm. These updates come in every twelve hours for several days leading up to it, and help departments make decisions about what clearing the snow will entail.

Part of this planning process involves employee schedules. Custodial employees add snow removal to their typical schedules, which for most is Monday through Friday, from 6 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. The grounds department changes its hours more often in order to adjust to snow predictions, often working through the night.

“Most people wake up at seven, eight, nine o’clock in the morning. “But we’ve been here physically removing snow since midnight, or since 10 p.m. at night the day before,” Lauzier said. “Most people’s days are starting, but we’ve just ended two days worth of work.” Before the storm, the departments also prep their equipment and “pre-treat” walkways and stairs with salt. Having this preparation before snow falls is important, Lauzier said. “What people don’t always see is the work that is done when it’s not snowing.”

Once the storm is closer or has begun, the Human Resources, Safety, and Auxiliary Services Departments assess and then make a recommendation to the senior advisor to the president and to the chief of campus operations about whether the college should call a snow day and officially close. According to Chief of Police John Carter, one of the many factors the college considers when deciding to close is “whether custodial and grounds are able to clear roadways, parking lots and walkways so that the community can move about the campus safely.” This constitutes the last part of the snow day decision-making process, as the departments usually determine whether or not they can clear the snow on time sometime in the early morning the day of the potential closure.

Even when the college decides to close, custodians and grounds employees still work because they are considered essential employees. During these official closures, non-exempt employees (including custodians, and typically other employees paid by the hour) get paid double time, two times their usual wage.

Employee A, a custodial employee who preferred to remain anonymous to protect their comfort in the workplace, said that on snow days, they usually feel like they are performing similar shoveling work for double the pay. “But,” they said, “if campus isn’t closed, and we are here [on our typically weekly schedule] … shoveling, we are just getting paid our hourly wage.”

For this reason, they also questioned the external considerations that go into keeping the school open, especially from the perspective of an employee whose pay doubles on a snow closure day. “For us, we’re like, ‘Why? Why isn’t there a snow day?’” they said.

Lauzier and Pereira, who supervise these employees, noted that while the large storms that usually lead to closures are always intense, smaller storms are usually more taxing on their departments. These kinds of storms make it harder to predict just how much snow clearing is really needed, and can end up producing a lot of work, Lauzier said. “Every time you plow it, white sticks to the ground, but when you don’t plow it, it’s never more than just that layer of white,” he said. “So you end up plowing nothing five times over and over for hours, and you’re just waiting for the last flakes to be done so that you can make that last pass and say alright, we’re done here.”

The snowstorm that occurred on Saturday, March 4, of this year was one such example, said Lauzier. Because the storm lasted for so long but never quite accumulated, he and the rest of the grounds team started clearing snow around midnight, and stayed until 3:30 in the afternoon the next day. “We got 2 inches of snow,” marveled Lauzier. “Thirteen hours of snow removal, and 2 inches.”

Lauzier and Pereira also said that some of the rarer, large storms are predicted to be so large that staff may not be able to drive from their homes to campus. In cases like these, they have the option to come to campus before the storm begins and stay to clear snow. Hourly non-exempt employees receive double and a half their usual pay rate for storms like these, because they are working on emergency closure pay and, after the first eight hours of work, overtime pay as well.

Pereira recounted a storm like this several years ago, when she was working as a custodian. Because the storm was so large, she and 17 other staff members arrived on campus at 5 p.m. and stayed until 2:30 the next afternoon, sleeping in an apartment in the basement of Charles Pratt Dormitory that was vacant at the time. Staff took shifts in order to continually keep clearing snow, and went to Val for coffee and meals. “To go into Val and see other people, [and ask], ‘How’s it going for you?’ ‘Yeah, it’s pretty bad.’ ‘You know, the wind is pretty crazy.’ It was just like a team. The sense of a team, it was there,” she said. Lauzier remembered a storm in February 2020 that also required staff to stay overnight. In the end, custodial and facilities cleared snow for a total of 72 hours because it just kept falling.

Clearing the Snow

In any size storm, grounds and custodial departments prioritize clearing snow from the areas that will be most heavily-trafficked the day of the storm. They use a list of events occurring on campus that day in order to plan effectively — for example, the walkways around the gym become more important if there is a game occurring that day.

For this same reason, the stairways and entrances outside dorms and academic buildings like the science center are also a priority. “If it snows, no matter what the case is, you’re responsible for maintaining clear sidewalks and stairs to your building,” said Bryce Benware, a custodian at the college. He described that this responsibility looks different depending on “how much snow we get, how fast it’s coming down, and when it starts.”

“If it’s snowing all day, then you typically would find yourself spending the majority of your day just shoveling. Because by the time you cleared your last place, your first place is already building up snow again,” he said. But if the snow is lighter or doesn’t continue for long, its impact is more just that he has to adjust his cleaning schedule slightly. “It does take away some of your time, so now you just gotta figure out how you’re gonna manage some of your time.”

Employee A mentioned the additional labor that shoveling adds to their responsibilities, especially when it is snowing heavily. “Physically, mentally, and emotionally. Your body hurts, you know? You’re already required to do a physical task inside, and then you’re outside,” they said. “It’s tough. And the clothing thing. You’re soaking wet, you’re sweating, you have to change … And then to come in and have to clean.”

Because custodians are responsible for both cleaning and shoveling around the dorm, Employee A described having to adapt their regular cleaning schedule in order to keep the walkways clear of snow. “You’re juggling running in and out to shovel … the entrances always have to be clear,” they said.

Employee B also said that while shoveling can be fun at times, “It’s super exhausting when you have to finish working outside in order to begin [cleaning] inside. There are times when you hurt your back from overwork.”

Given the tax of this additional work, “We don’t get paid accordingly,” said Employee A. They noted that oftentimes custodians do not come to work with proper attire to be shoveling outside all day. If employees from an outsourced snow removal company came to clear the snow, Employee A said, they guess that they’d be paid more than custodians do for their work. Employee B agreed.

“I think we should be paid more. Because we add more work to our shift. Remove all the snow, sprinkle salt, and then we have to clean the buildings inside,” they said. “Our work is on the rise but our salary is not.” Employee B noted that they see these feelings as common among their coworkers, too. “I don’t only speak for myself,” they said.

Benware said he personally only notices the extra burden when it’s snowing heavily and he has to spend the whole day shoveling. The lighter snow responsibilities are something he signed up for on the job. “And what I think it really comes down to is just making sure that everyone who has to walk across the campus is safe,” he said. “I don’t really think … much thought goes into ‘Oh, their workload is bigger,’ or ‘Oh, let’s lighten it a little bit.’ No matter what, we gotta do the work. It’s about the people who are using the campus and the facilities, and just keeping it safe.”

Employee A, meanwhile, said that preparing for snow adds stress to their life. “When you’re preparing the night before for a storm, you’re thinking about yourself, your home, your family, and then you also have to think about the work aspect of it,” they said. “Is your family going to be safe? Are you going to have power at home? And you have to shovel your way out of your home to arrive here on time.”

Employee A cited this as another reason why they would often prefer the college to call an official snow day closure even if it may be physically possible for staff to remove the snow while keeping campus open. This way, essential staff could take more time to safely commute to the school, and would have the flexibility to take more time to clear snow. “We wouldn’t feel as pressured and anxious to actually have to do all of it. We’d get it done, but it wouldn’t be as much pressure,” they said.

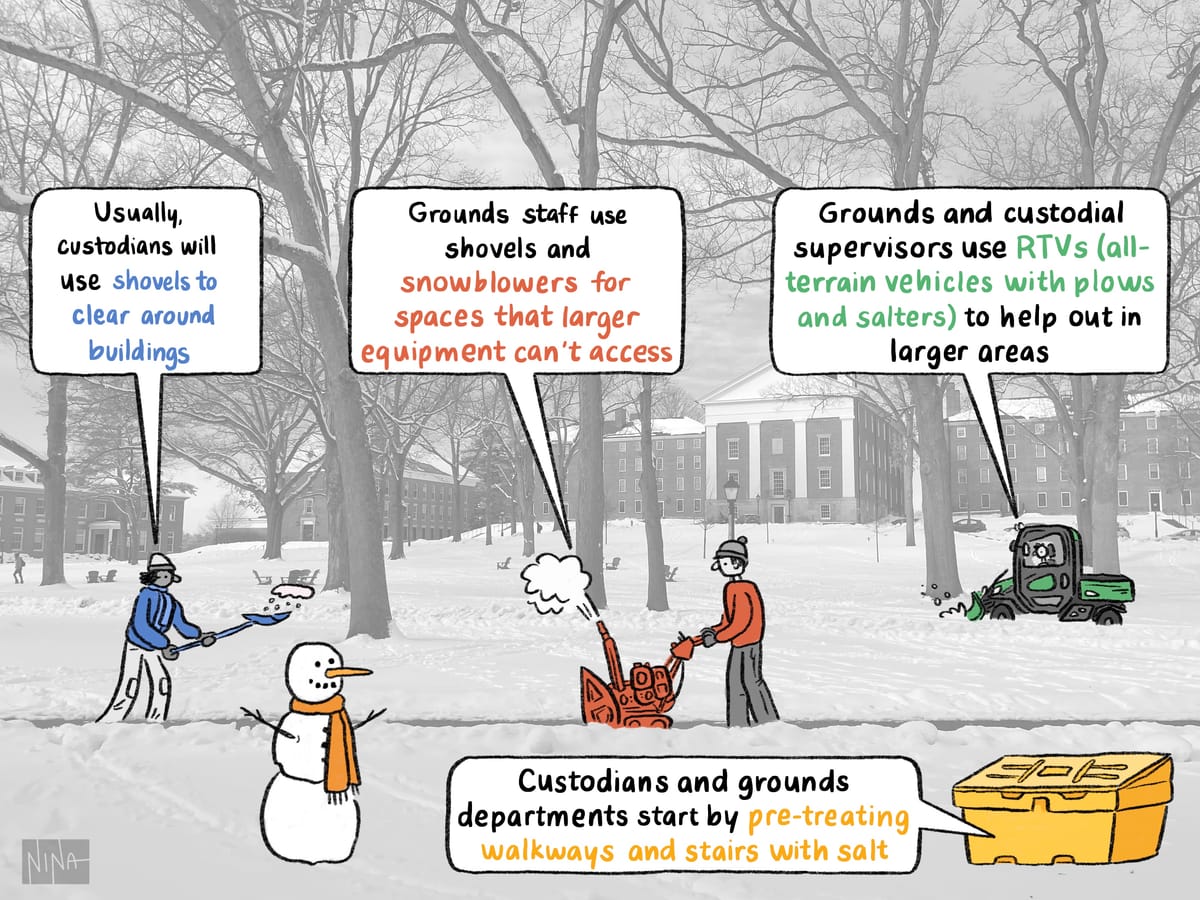

Custodians use shovels to remove snow around buildings, while supervisors use RTVs, all terrain type vehicles with plows and salters, to help out in these same areas. The grounds department uses two large construction loaders for the main roads and parking lots, Bobcat toolcats for the main sidewalks, and their own RTVs for buildings, patios, crosswalks and dumpster areas.

Additionally, grounds staff use shovels and snowblowers for areas that larger equipment can’t access. Both teams also use salt, which makes snowy areas less slippery by creating “a barrier between the snow and the roads so that there’s a minute layer of melted snow [so] that the snow can’t stick to the asphalt,” Lauzier said. “Think of Pam in your pan when you’re cooking.”

eAfter a storm is finally over, the departments take a day to decompress — Lauzier calls that the “24-hour rule.” After those 24 hours, the custodial and grounds teams reconvene to discuss how the process went. “What was successful? What wasn’t successful? What do we need to do better next time?” Lauzier said they ask. “We don’t want to be the kinds of teams that draw, literally, lines in the salt and say, ‘I do this to over there, and you do that to over there … ’ We have those conversations frequently to make sure that we’re not opposing each other, and we’re helping each other. Because we are here for the same task.”

A Deeper Understanding

Employees also reflected on the stories and place-specific knowledge that comes with the job of snow removal.

Lauzier has observed small microclimates within the Amherst campus itself. For a reason that nobody is quite sure of, snow seems to behave differently on the main quad than it does at the Science Center. “I’ll see snow stick to the main quad sidewalks before it sticks to the Science Center sidewalks,” Lauzier said. “Even within campus, [there are] pockets.”

He noted the importance of using a range of weather sources. For trustworthy information about the Pioneer Valley’s local weather patterns, Lauzier says he follows Dave Hayes the Weather Nut, a local man who is not formally trained in meteorology but has extensively educated himself about weather. He posts forecasts on Facebook and, as Lauzier put it, is “more accurate with weather forecasts than any legitimate meteorologist.”

Hayes refers to Amherst as part of “the snow lover’s triangle of disappointment” because of its low snowfalls in comparison to surrounding areas. The March 4 snowstorm, for example, dropped 3 inches in Amherst but 8 in Northampton. Lauzier recounted an even more extreme instance in March a few years back, when weather forecasts predicted three consecutive storms that would drop around 18 to 24 inches of snow in the region. While Pelham, which is about 8 miles away from Amherst, got almost 30 inches of snow in the storms, Amherst got less than 3.

Pereira mentioned the new ways you come to see campus after having experienced plowing snow on its pathways. For example, the patio behind Johnson Chapel, and the one between James, Stearns and the Mead are known to be difficult for plowing because they are hard to navigate and are unevenly paved with stones. Before recent maintenance and repairs on the main roads on campus, too, Pereira and Lauzier recounted the common experience of hitting a small, obscured bump in the road while plowing. For example, if there is a small manhole in the road, “you’re just plowing, and plowing and plowing, and … a plow doesn’t just glide over that. You crash into that,” said Lauzier. “And somebody watching you just sees you hit nothing in the road, but your whole plow goes five feet in the air.”

Pereira said that inside jokes and a community form around common experiences like these. “After we go around and we plow, then we go back to the office, and we sit down and we start talking,” she said. “‘Oh my god, you’ll never believe what happened to me, I was plowing and all of the sudden, the plow hit this stone … ’ ‘Did you go there?’ ‘Were you able to plow?’ Things like that, telling stories about what happened.”

Benware said he looks at snow, and the responsibilities that come with it, as one part of a job that changes with the seasons. “In the fall, you’ll end up getting all sorts of leaves and pine needles tracked into your building, or blown in through the wind. In the spring, you end up with muddy footprints all through your building, from people out at the sporting fields … In the summer, it’s the pollen,” he said. “Every season has its own thing.”