Published in The Amherst Student on April 20, 2022

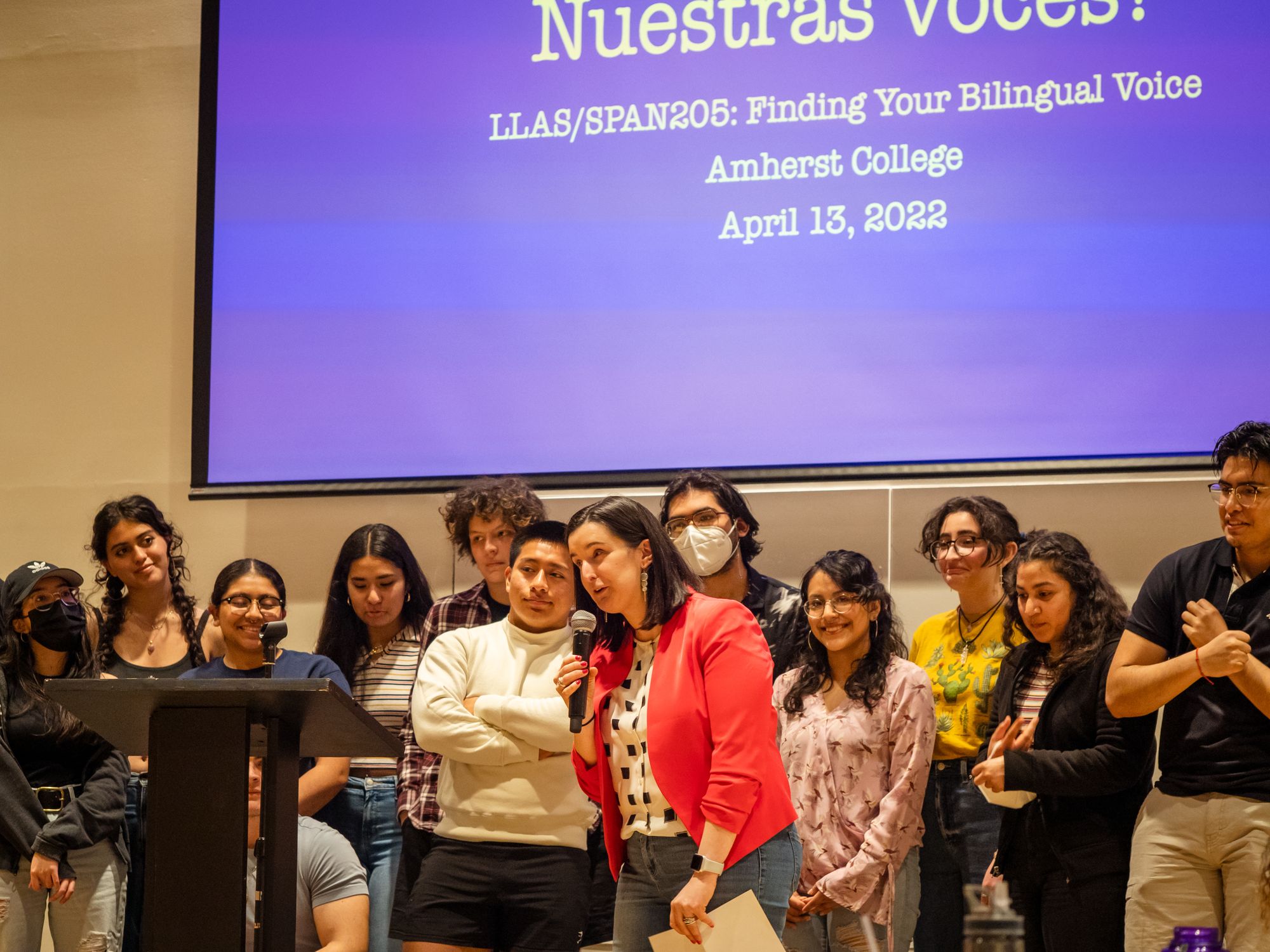

On Wednesday, April 13, 16 students presented poetry, videos, and art for the inaugural “Nuestras Voces” (“Our Voices”) event, organized by Senior Lecturer in Spanish Carmen Granda and her students in LLAS/SPAN-205: “Finding Your Bilingual Voice.” Taking place in the Ford Event Space with an audience of over 60 community members, the event was co-sponsored by the Spanish Department, the Latinx and Latin American Studies Department, La Causa, and the Center for International Student Engagement. In both English and Spanish, students spoke about topics including connection to home, the value of names, and gentrification of neighborhoods.

In an interview with The Student, Granda explained that the idea to hold an event empowering bilingual students came to her at the beginning of the semester. “The goal was to celebrate different voices in English and Spanish, through different mediums and genres and to lift each other’s voices up, because it is a very vulnerable act to write, and then, to share your work,” she said.

Ellerman Mateo ’25, who read his poem titled “501 Years to Mateo,” reflected on the success of the event, which he said was both “truly transformative” and “a platform.” He explained that he admired “how transparent and free people were with their language,” and the idea “of infusing Spanish into your poem.”

“Everybody just let go of their guard, and just spoke from the heart about what they had to say. And [we] were proud of it,” he said.

Angelina Suarez ’25, who read her poem “Ode to Home,” reflected on the vulnerability at the event. “Just to even go up there and present … that takes a lot to do in front of a lot of people,” she said. “Seeing the presenters smile every time, as they got off the stage, they were always smiling, I noticed … it helps to uplift you knowing that you’re being recognized, that you’re being validated.”

Granda noted that the event was also about identity within writing. “I did this because when you write about yourself, you’re giving yourself permission to express your own voice, your own ideas, your own story, in your own language,” she said. But writing by itself, she reflected, is “not enough to find your voice. It’s really important to practice listening to the sound of it. It gives it more meaning when you find that sound, refine your style — there you’ll find your story.”

For many students, the event was significant because it allowed them to weave Spanish and English together and work between the two languages. “Being a Spanish speaker myself, there are some phrases in Spanish that you just cannot express in English,” said Mateo. “One word in Spanish could mean a sentence in English.”

“Whenever [people switched] to Spanglish, it was almost like a song,” Mateo added. “It flowed. Spanish is a language that can flow whenever you speak it … like a good poem, and then English, it’s almost like a song.”

Salvador Malagon-Martinez ’25 read his poem titled “Mar y Flor,” which covers the power of love, and unreciprocated love. “Me ahogue / Dentro de los siete mares de tus ojos tan bellos / Mi corazón, / Naufragó contra los contornos de tu ser,” the poem reads.

Malagon-Martinez reflected: “The experience was really impactful and makes me want to possibly pursue [poetry] even further, maybe be more active here in the poetry scene at Amherst,” he said. “Everyone was really receptive to it. Here … the arts are really valued among the student body … I really love that about this place.”

In her poem, “Ode to Home,” Suarez wrote on the love and complications of home, and her “different definitions of home,” which she characterizes as “my actual home, like where I’m from,” and “my home here, like my found family.” Her poem begins: “Home. / Home is the 90-degree dry heat of a Texas summer day.”

She continues: “A synonym for home that people tend to forget is expectation. / Just as the last two ice cubes are clinging to each other, trying to survive the summer heat, / You are left trying to endure the constant scrutiny of your Latino parents.”

Reflecting on her writing process, Suarez said, “I think writing it out was really good for me, just because … I had never talked to anybody about it before. That was kind of like an outlet to get that out of me. And just let it go,” she said. “Whenever I was writing it out … I could feel like a weight was coming off [me].”

Speaking on his poem, Mateo explained that he chose to write something where “the poem actually jumps back in time,” to explore the origins of his name, which is “a common name,” but “when I started to look deeper [I found out it is] based on colonialism.”

“The Gods you worshipped were blasphemy to the one and only God / They proclaimed salvation, eternal life, and yet malice lurked behind their white skin / You are to take the names of their religious figures,” the poem reads.

Piero Campos’ ’25 poem “The Little School in the Hood that Could” is based on a phrase that he and his classmates would use to speak about their middle school, a rhyme that “reflected not only our struggles, also our hopes and dreams for better lives through the power of education,” Campos said.

The poem reads: “Rather, I want to give hope that was once given to me before I left. / So it’s my time to spread the word about the little school in the hood that could. / Cuz it ain’t got to be a place filled with theft / It just has to be a place filled with hopes and breaths.”

Amelie Justo-Sainz ’25 wrote about her home, the Mission District of San Francisco, California, and the impacts and violence of gentrification there. “Adelante! / Mira a los bright murals that show what you’ve done to my people / Drink from the cafes that have displaced la Doña’s panaderia / Eat from the restaurant of a culture whose people you want to keep out con fronteras / Pero esas fronteras seem to magically disappear when it most benefits you,” she wrote.

“Nuestras Voces was an amazing opportunity for me to express myself creatively … Being able to switch between my two languages was also very empowering,” Justo-Sainz reflected.

Speaking on the event as a whole, Granda spoke on the importance of exploring and embracing bilingualism. Her class, LLAS/SPAN-205, is for “students who are considered heritage speakers,” which means “people who grew up either listening or speaking Spanish with their families or their communities … Within this group, though, there are various levels of Spanish proficiency,” Granda said. The Spanish department is currently working on developing a heritage language program, starting with SPAN-205 and SPAN-105: “Spanish for Bilingual Students,” which will be offered in Fall 2022.

“I saw the whole process. In class, they were exploring. They were processing. And … they’re ultimately deepening their understanding of what it means to be bilingual,” she said.

“[In] class where we’re able to talk about our insecurities, like ‘I’m supposed to be bilingual, but maybe I’m not necessarily entirely fluent,’” said Suarez. “The class made me realize that [this isn’t] something that only I go through.”

“I feel like the event just reinforced that because it showed us … your voices do matter. Even if you can’t pronounce the word right,” she added.

Similarly, said Mateo, “It’s a way for us to feel more connected to who we are … By having that, we can travel between two worlds, from the Spanish world to the English world.”

At the end of the event, Granda stepped onstage to deliver her own poem, “Oda a mi clase,” which, to the surprise of her students and the event participants, was a combination of all the pieces that had been shared that night.

“I wanted to write my own poem, but after reading all their poems, I was intimidated and I couldn’t come up with anything,” said Granda. “But I thought [combining everyone’s voices] was powerful because it reinforced the value of community,” she said.

Granda reflected on what the event meant to her as a heritage speaker herself. “Once a heritage language learner, I never had the chance to take such a class; so now, as a teacher, I am sharing moments with my students and giving them the opportunity to express themselves in a way that I wish my instructors would have. It feels full circle,” she said.

“Being bilingual is a gift.”